what he can play for you

what he can play for youif we think of noise in the

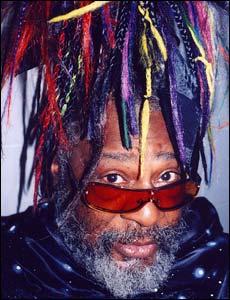

attalian sense--as a new organization of sound which serves as a harbinger for a new social order--and we recognize that hank shocklee truly

brought the noise back in the mid- to late-80s (and surely continues to), then we can indeed consider

shocklee to be a prophet of sorts. and though he speaks volumes through his music, and perhaps communicates more powerfully and directly with beats than with words, shocklee is an eloquent spokesman for sample-based music-making even when he's not behind the boards.

monday afternoon, at the

future of music summit, i had the pleasure of listening to hank shocklee have a candid conversation about sampling practices and copyright with none other than george clinton, hip-hop's

samplee par excellence (alongside james brown, of course--or perhaps, more precisely, the

funky drummers themselves).

clinton offered a humorous, self-deprecating theory for why his music appealed to producers such as shocklee: "we made cheap sounding records; not a lot of EQ on it, so it left room for hip-hop."

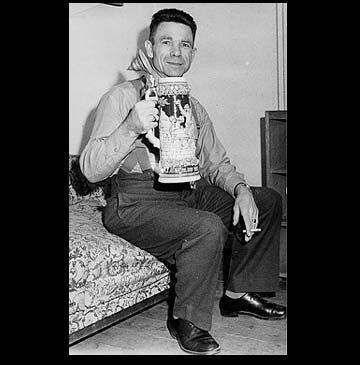

shocklee made sure to counter any such humility on clinton's part. "there are three, i think, most important figures in black music," he said, "1) jimi hendrix, 2) james brown, 3) george clinton." shocklee elaborated on clinton's contribution in particular: "you fathered alternative rock'n'roll," he told the flattered parliamentarian, "your whole approach is rock oriented; you also are the developing godfather of hip-hop--[your music] had an edge and a feeling to it that is reminiscent of hip-hop."

for his part, clinton pre-empted shocklee's praise by setting the record straight before the bomb squad member was even brought on stage. challenging the common complaint that sampling is a product of laziness, clinton emphasized that "hank shocklee is not lazy." and regarding the use of samples in music production, he continued: "it's probably twice as hard to make 'em blend, all those atones and different keys." (i love that term,

atones, especially as

intoned by dr.funkenstein.) moreover, clinton noted, he himself had been saddled by similar criticism, and from close quarters at that: "my mother called us lazy, too. she said we vamped." by recognizing the similarities between vamping--i.e., playing the same groove for an extended period--and sampling (both of which share an utter revelry in repetition), clinton sought to draw an important, and too often overlooked, lineage between his own music-making approach and shocklee's. "it's just a new way of making music," he said of sampling, matter-of-factly. and the more that the old guard huffs and puffs, the more the next generation will cut'n'paste, chop'n'stab, and mix'n'mash. or in clinton's words, "kids love it when you hate it."

of course, most people know that george clinton has been in favor of his music being sampled for some time. he himself admits that, referring to hip-hop's use of his catalog, "it was a way to get back on the radio." clinton released a

set of three CDs back in the 90s precisely for the purpose of making samples of his music available, and at reasonable, sliding-scale rates ("if you sell, you pay, if you don't, you don't"), to those who wanted to sample it. he mentioned that "they're used more now than they were back then," since, interestingly, back then most sample-based producers thought that using such discs "was too easy," too "overt."

ironically, clinton was sued for issuing these discs by

a company that claimed (claims?) to own his music--a company that, moreover, is now litigating hundreds of similar suits against sample-based artists, but NOT on behalf of the musicians being sampled.

moderator

rick karr asked clinton, "how did you lose the rights?"

"they stole 'em," he said. fooled him into signing some pieces of paper. "if you don't have money," he explained, "you can't go to court." plus, he was often on the road, he admitted. at any rate, once he had the means and time to sue for his rights, "the judge heard my side of the story. ... and he told 'em, 'get out.' give me my songs back. it was that easy." (of course, if he did get his songs back, one wonders what the

three-notes decision should mean at this point. then again, one wonders what it should mean at any rate.)

clinton has repeatedly made it clear that he does not support the litigation of sample-based artists supposedly on his behalf. when terminator x sampled from "body language," he was sued for $3M and clinton was fingered as the instigator of the suit. clinton told the audience that he went on CNN with chuck d to make clear that he wasn't suing PE. according to him, the case was subsequently dropped.

shocklee, who had just joined clinton on stage, asked "who makes the money?" in such cases.

clinton replied, "

that guy suing for $3M. he's got 400 cases in tennessee right now."

(i love that term,

that guy.)

shocklee added: "we [PE] paid a lot of money to bridgeport. and we're still paying."

for all his gripes, though, shocklee had some pretty straightforward suggestions about how to improve the system. one of his repeated requests--a compulsory licensing system of sorts, or at least a more navigable, transparent, and consistent system of pricing--was an oft echoed call throughout the conference. even as shocklee urged the creation of such a thing, though, he acknowledged the inherent difficulties of setting it up.

"is there some sort of menu list?" the veteran producer asked, semi-rhetorically. but then he wondered aloud, "do i pay the same amount for 40 seconds as for 1 second?" and while noting that "there obviously needs to be a line that needs to be further developed," shocklee complained that a system with "no parameters, no rules" puts sample-based artists at an unfair disadvantage.

the copyright industry (and, yeah,

industry seems like the best way to think of it in this context--it's not really about paying musicians here, izzit?) needs to recognize sampling as a commonplace and equally valid approach to music making and needs to stop asking for exorbitant, extortionary licensing fees from artists who must, let's remember, seek out this information themselves, often from multiple sources (which are not easy to track down), and cut a deal with each and every one of them (including the owners' of the publishing rights for the underlying composition and the owners' of the mechanical rights to the master recording). how's that for bargaining power?

as shocklee put it, "it's very irresponsible to say someone has to pay for something without telling them how much it will cost."

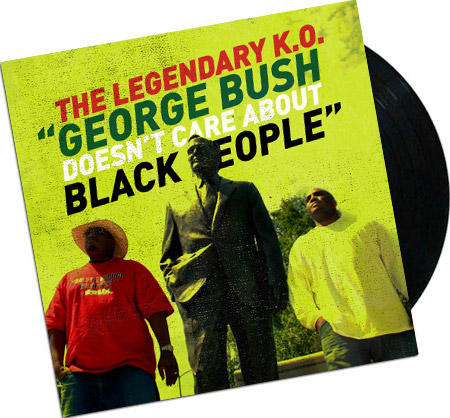

the days when the bomb squad was crafting such sample-heavy masterpieces as

nation of millions and

fear of a black planet were a time when, shocklee argued, "it wasn't really clear" what the rules were with regard to sample-based music, especially for beats comprising dozens of small, often unrecognizable samples. hence, shocklee wonders: "should you be allowed to go backwards and sue people retroactively?"

during the early years of the "golden age," before a series of debilitating lawsuits sent a chill through many a hip-hop producer, PE's music brimmed with samples enabled by new technologies and fostered by new traditions (which were, in part, rather old traditions in new contexts). the bomb squad produced and released a lot of music in those days that would, at least according to hank

shocklee's sense of it, never get made in today's litigious world. thus, we have to weigh the social and cultural costs of this situation. ask yourself the

frank capra question: would the world be better off without

nation of millions? (the answer is obvious, no?)

how one prices different types of samples--from the smallest fragments to longer loops, from hooks to intros to incidental passages, from recognizable forms to essentially unheard shapes--is a tough question but, for shocklee, one that demands an answer: "i think that there's different pricing" for different uses, he argued, "and the publishing" should reflect that. "you're only allowed 100% of publishing," he explained, seemingly stating the obvious. but with three people suing him for 40% of publishing on a single track (and let's remember that PE tracks often contained dozens of different samples), that adds up to an impossible 120%, with nothing left for his own efforts.

"if the sample only constitutes 1/8th of the song," he offered by way of example, "then how does that justify 50% of the publishing?"

arguing for the sampler-as-instrument, shocklee wanted to stress that a particular

performance--the presumably 'original' materials for which one might hold a copyright--is not always what sample-based producers are looking for: "sometimes we sample because we just want the sound." he offered an example to clinton: "you've done some incredible things with the moog synthesizer in terms of filters, effects [etc.] ... in order for us to get those sounds today [is impossible]."

this is what i have

tried to argue as well: that producers don't sample a breakbeat, for instance, because they want the particular rhythm so much as the

timbre--the distinctive

quality of the sound that is found only on that particular recording (and usually has more to do with the recording equipment, the room, the instruments, and the engineers than the songwriters or musicians--who really

does own a phil collins snare hit?). for shocklee, sampling opens up an irresistable and unique sonic palette, and one that hip-hop could no more easily abandon than rock'n'roll its fender or gibson guitars. if, as shocklee says, "everything [in music] has been done," what does it matter whether one plays a particular musical figure with a guitar sound or with a processed sample?

"sound is about character," said shocklee, "and the character of the sound is more important than the sound itself." and though this means that, to some extent, sampling is "about capturing that vibration that [clinton and others] developed"--and extending it--"there's a difference between sampling the performance and sampling a sound."

"when we sample a sound," shocklee contended, "we're going for the actual frequency." sampling today, at least for him, is "not taking the entire sound, it's more like taking a piece of it." to demonstrate his point, shocklee chopped up the intro to parliament's "flashlight," taking a drumroll with some guitar in it and repeating it a few times with some rhythmic stabs.

"how much should i pay for that?" he asked.

clinton laughed.

+++

in a subsequent session on sampling, where shocklee was joined by

jeff chang,

siva v,

shannon emamali, and

bob kohn (who wrote a book on music licensing but admits an utter lack of familiarity with the music of PE or jimi hendrix), jeff chang noted that sampling laws have "created two classes" of sample-based producers: the "super-sampler class" (i.e., diddy, kanye) and the "outlaws." part of the "outlaw" class is made up of mid-level artists, "a real small and shrinking middle class," who, "more and more constrained by what the laws are," have the sales to get noticed by sample-sniffers but not the $$$ for licensing fees or "transaction costs" (which siva unmasked as "fancy words for lawyers"). but there are also, by jeff's count, "a lot of folks [sampling] on the indie level."

and just as the vast majority of copyright holders are not, as the RIAA would have you believe, signed to major labels, the vast majority of sample-based music is unlicensed and thus--as some would have you believe--illegal. for jeff, this has more to do with hip-hop's essentially oppositional aesthetics: "hip-hop is not asking for any kind of OK to do something," he noted. and i think there's a lot to that. i think, indeed, that hip-hop's aesthetics and ethics vis-a-vis sampling have traveled beyond hip-hop's socio-cultural and musical boundaries and have found adherents worldwide and in the darnedest places. we live in a sample-based musical world at this point. all genres employ samples and some rather explicitly (jungle, b-more breaks, NOLA bounce, funk carioca, etc.). and the mashup is here to stay. it is but a matter of time before the law reflects popular practice on this point, i would say. (other longstanding

legalization attempts notwithstanding.)

i attempted to allude to this inevitable sea-change during the panel on "transformative use" that i sat on alongside

kembrew macleod, the guy who trademarked the phrase

freedom of expression, and

lawrence ferrara, the guy who defended the

beasties against james newton. i'll share a version of my opening remarks in my

next post, but the gist of my argument was that transformative use constitutes a fundamental and ubiquitous approach for making music. within this broader understanding of the way music is made, sampling should be considered--at least as far as the law is concerned--simply another transformative technique along a spectrum of transformative uses. to treat it otherwise and to penalize, restrict, and repress such an essential method amounts to a grave misunderstanding about the way music works. new technologies enable new transformations. and culture understands this. hip-hop certainly understands this. but culture and hip-hop don't seem to matter much in court, so the law at this point remains out of step with popular practice. (and, i have to say it, probably racist, too, as the norms for what constitutes "original composition" remain as enmeshed in the values of western european art music as music departments in american universities remain committed to the very same [marginal] repertory.)

a lawyer in the audience took issue with my declaration of the law's out-of-step-ness. on the contrary, he noted, the law has very clear rules about what is allowed and what is not and it has, for instance, added mechanical rights to copyright claims in order to keep up with new technologies. moreover, the court system has often upheld a defendent's rights against a copyright owner's claim (as in

newton v. diamond, where the issue revolved, however, around publishing rights rather than mechanical rights). sure, i guess so. but who makes these rules? (musicians?) and who benefits, on the main? and who does not? when we look at what's happening today, do we truly behold a system that works? a system that incentivizes creation and facilitates a robust cultural system where creators can proceed to make art as they always have (i.e., by transforming other art)? a system that is consistent with commonplace attitudes about ownership of media and information?

another audience member argued that so-called standards of compositional originality in these cases failed to recognize the improvisatory compositional methods of jazz. i added that the same is true, more or less, for hip-hop: that there is a basic lack of respect for the validity of the form, a lack of respect which reveals itself in establishmentarian strictures and discriminatory punishment. (this is why--at least one reason why--hank shocklee calls mechanical rights "a scam.") but at the same time, i added, that only goes for the establishment. at the level of popular practice, kids are mashing up the place. sampling is rampant. in fact, the level of unlicensed sampling and the egregiousness of the length and reconizability of the samples is at an unprecedented level. between indie hip-hop, indie everything else, mashups, mixes and mixtapes, cell phones--you name it--there's a whole lotta sampling going on. it's only a matter of time before law and policy adjust to the reality of the situation. (only, why don't they make it quick so we can stop paying all these lawyers?)

i'm not sure that i convinced everyone in the room, despite the preaching-to-the-choir vibe of much (but not all) of the conference. there were certainly lawyers and fogeys and others who didn't really nod along. but then, in the front, there were some young people. and they were smiling. and one of them gave me a CD full of

sample-based beats that bristle and bang and defy attempts to pin them down. the music twists and turns, away from law and away from convention. which is wonderful--but i don't think all sample-based music should have to sound this way. referentiality can be a really rich, resonant experience in music. so much of what makes a track great is the way it refers to, evokes, grows out of, and inspires other tracks. intertextuality is at the heart of hip-hop, reggae, and, when we think about it, just about every style of music, to a lesser or greater, more implicit or explicit, extent. we can't afford to lose that. we

can't lose that, really. but we can't tax people on it either, at least not according to the current system. (and let's face it: despite the allures of a fully transparent, sliding-scale structure for compulsory licensing of samples, such a project represents an organizational nightmare approaching the impossible.)

+++

siva put it well, and brought things into focus, on monday afternoon when he said: "the creative work that copyright law should be concerned with is the work yet to be created."

and earlier that day, hank shocklee put it better when he sliced up an even smaller bit of parliamentary funk, looped it, discussed filtering it and transforming it into more of a "pad" sound, removing the digital glitches, and composing anew with it. he turned to george clinton again and asked him: "how much should i pay for

that?"

clinton put it best of all, perhaps, when he replied: "it gets deep."

no doubt. but if we don't dig deep on this issue, i fear we'll be missing some real treasures.

who did that letter say were suckas?

who did that letter say were suckas?