wicked wicked soundscape

gettin' jiggy at 3 C's (photo from bobbyshakes.com)

since i'm in a snipping mood, i thought i'd share another piece i wrote recently. the following was published in the july issue of sonicheart, a new boston-based music mag specializing in the "electronic" scene--an umbrella term seemingly encompassing just about anything that can qualify (which is an interpretation that i obviously endorse). in keeping with that inclusive mission, the sonicheart folks asked me to contribute something about boston's reggae scene. despite a general degree of acknowledgment (and even genuflection, at least to the dub guys) in the electronic music lit, the prevailing impression seems to be that reggae, and generally other "black" musics, aren't electronic. they're organic or something, natch. (and actually, natch more-or-less says it, fingering the naturalization, romanticization, and condescension implicit in the myth of inherent "black" musicality.) but, of course, as many have pointed out, you would be hard-pressed to find music in which technology plays more central a role than it does in reggae and hip-hop.

as a kind of tangent to my dissertation, i've been interested in the boston reggae scene as an example of reggae in the diaspora. what does reggae carry with it? what do people bring to it? in this way, i see reggae's resonance in the U.S. as an interesting flip-side to hip-hop's significations in jamaica. although i'm hardly old or experienced enough to be able to say anything definitive about boston's reggae heritage, i've been talking to and interviewing (and spinning alongside) folks in the reggae scene here for several years now. and i've been absorbing the sounds of jamaica, consciously or not, all my life in and around boston. moreover, a number of boston reggae veterans have been kind enough to offer up informal histories, favorite details, and reminiscences of all sorts. (note the acknowledgments at the bottom of the article; and thanks to all the others who have spoken with me or otherwise shared their memories and opinions.) to the extent that i get some things right in the brief history below, it is to their credit as bearers of their stories. any mistakes or glaring omissions are my own. ultimately, i hope that efforts such as this one can encourage others to continue building this history, this tapestry of cultural connections, musical memory, and commuity spirit. i invite any and all to help flesh out this skeletal account, to keep dubbing in new voices.

finally, a word on my frame here: knowing my audience and my limitations, this piece is written as an introduction and a primer. it is intended for the boston-area music enthusiast who would like to experience the reggae vibes around town, who may not be aware or cognizant of reggae's rich resonance here, and who thus might think a little differently about their community and its history--and hear the boston soundscape anew--as a result of (re)considering this town's roots-and-cultural heritage.

[snip]

Reggae-Tinged Resonances of a Wicked Wicked City

Boston is well-known for using wicked as an adverb, as in "It was a wicked fun pahty" or "Wicked pissah, dude." And while Bostonians use wicked as an adjective too, it is more commonly found as an adjective in Jamaica, where, although tied to Biblical curses, when used colloquially the word is synonymous with other re-signified terms of praise--e.g., tough, bad, mad--as in, "A wicked tune that!" or "Wicked inna bed." So, if we're talking about reggae in Boston, wicked wicked emerges as the perfect modifier for what is a vibrant, diverse, and established scene.

Although reggae may not be the first music one associates with Boston, the sounds of Jamaica have long been part of the city's soundscape. Known for its large number of venues and college students, Boston has been a destination for touring reggae acts since the 1970s. For years 88.9 WERS has played reggae from 5-8 p.m. every weekday—perfect rush-hour listening—on its "Rockers" show. And with the continued and increasing crossover of dancehall into the American mainstream, one now hears a fair amount of reggae on Boston’s hip-hop and pop radio stations as well. At times Boston audiences have even displayed a cultish love of reggae: The Harder They Come, which introduced Jamaica's music to the world as much as Bob Marley did, famously enjoyed one of the longest cinema runs in history at the Orson Welles Cinema in Cambridge during the 70s and 80s.

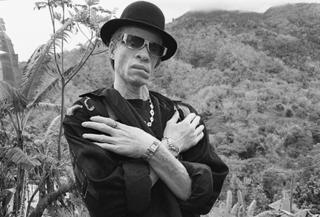

For some Bostonians--in particular, the predominantly white baby-boomers and generation x-ers that form the core of the live-band audience--reggae signifies sun, fun, rum, and ganja and provides a compelling soundtrack for shaking out their stiffness on weekend nights. For hip-hop DJs and audiences, reggae is a familiar, related, and sometimes nostalgic reference, and a hip-hop set at a club often includes some dancehall tunes. For DJs in the ragga/jungle scene, reggae is a creative resource, something to be sampled, remixed, and played against double-time breakbeats. Playing dancehall a capellas against a barrage of breaks, these DJs pay tribute to jungle's roots in London's reggae scene and align themselves with reggae's oppositional sentiments. For the more purist DJs, or selectors, who play reggae exclusively, the music is a world unto itself, a vehicle of righteousness or licentiousness--and sometimes both--and a means of identification with a larger community: with Jamaica, with the Jamaican, West Indian, Caribbean, and/or African diaspora, and with reggae enthusiasts worldwide.

In the early 1980s, Boston's reggae scene was blessed by a number of soundsystems and selectors working mostly in clubs in Dorchester, where Boston's West Indian population has been based for decades. Echo International (which later changed its name to Capricorn Hi-Fi), with its eponymous selector, Echo, was one of the more well-known sounds in the area. Evertone Hi-Power, with selectors Wheely and Robot, ranked among the best in town and is remembered as one of the biggest soundsystems in Boston during the 1980s. They even clashed with legendary Jamaican sound, King Jammy’s, in Dorchester in 1986. Apparently, Unity Sound, with selectors Reggie Dawg and Warren, was the "gal favorite," while Supersonic was known as the "bad boy" sound, with connections to the infamous Dog Posse. Cambridge’s Western Front earned a reputation in the 1980s as a spot for "bad men" as well as for serious reggae music, especially from local live-bands such as the I-Tones and Cool Runnings. Aside from the Front, though, most of the top spots to hear reggae in Boston were based around Blue Hill Ave in Dorchester: Black Philanopies, Manny's Bar, Windsor Cricket Club, 4 Aces, Carver Lodge, Kelekos, and, of course, 3 C's—the Caribbean Cultural Center, which opened on 1000 Blue Hill Ave in 1981 and has been hosting big reggae events ever since. Veterans of the Boston reggae scene also note the popularity of house parties during the 80s, many of which, not unlike dances in Jamaica, would often last until 7 or 8 in the morning.

Iranian-born, London-bred, and Boston-based selector extraordinaire, Junior Rodigan, cut his teeth on the house party scene. He began his local music career in 1986, DJing parties for friends at B.U. Before long, Rodigan worked his way into the reggae scene, playing at clubs and after-parties and making a name for himself as a selector with deep crates, extensive knowledge, and a fine sense of a crowd's mood. He produced and performed on some recordings in the late 80s, such as "Get Here (If You Can)" with Igina, which stand among the few reggae shots from Boston heard around the world. Having watched reggae go from marginal to mainstream in Boston, Junior has a unique perspective on the history of the scene. At one time, he recounts, a reggae set at a party could leave a dancefloor empty and indifferent, whereas now reggae is just another part of the mix--and often a popular, if not crucial, part. "It's come a long way," Junior told me, "but it was inevitable." Comparing Boston’s socio-cultural milieu to London's, where he spent his teens, Junior attributes the shift in taste to basic demographics: "Just like in England, there's all these West Indian kids who grew up here now. And at that time [i.e., the mid-80s] whoever was twenty-one hadn't really been to school with too many West Indian kids. The West Indian kids had just been getting here. Now, whoever's twenty-one has been to school with West Indian kids since they was six." Indeed, a Boston-area education specialist estimated back in 1995 that as many as 70 percent of children in the Boston Public Schools were of Caribbean descent.

My own memories of reggae in Boston definitely resonate with Rodigan's remarks about the relationship between demographics and culture. Sure, at a certain point I learned about Bob Marley and roots music, but my first exposure to reggae was via hip-hop. The first "reggae" song that I can remember listening to is the bizarre hybrid, "Roots, Rap, Reggae," featuring Yellowman, on Run D.M.C.'s King of Rock (1985). A few years later, I heard more reggae-tinged rap from Boogie Down Productions, Shinehead, Slick Rick, Special Ed, Leaders of the New School, the Fu-Schnickens, and other acts. Before long, dancehall reggae artists such as Super Cat, Shabba Ranks, and Chaka Demus & Pliers began reaching me through hip-hop vehicles such as Yo! MTV Raps and Rap City. High school dances at C.R.L.S. frequently featured the sounds of Jamaica, as the DJ--usually my old friend, K.C. Robinson--would segue at a certain point from the rap and R&B hits of the day to some real windin' and grindin' music. Mad Cobra's "Flex" was a favorite back in those days (for obvious reasons if you know the song). Incidentally, K.C. was one of the first DJs involved in the now longstanding Monday night session at the Phoenix Landing in Cambridge that mixes hip-hop and reggae (although these days, revealingly, the hip-hop portion has been shaved down to a mere 1/2 hour).

When I returned from a six-month stint in Jamaica a couple years ago, I felt as if reggae had followed me home. Although reggae continues to grow in popularity across the U.S., my perception was largely due, I think, to a greater sensitivity. Hearing reggae in the Boston soundscape is all about tuning your ears to its distinctive vibes: it's definitely out there—on the airwaves, in passing cars, in clubs, and sometimes on flatbed trucks. There are reggae events every night of the week in Boston. (Just check the calendar over at bostonreggae.com.) While the Phoenix Landing in Central Square hosts "Makka Mondays" with Satellite Sound, across the street at the Enormous Room (where DJ Brynmore and Burning Babylon just started a weekly dub session, "Heavy Dread," on Wednesdays), the eclectic duo of DJ C and DJ Flack mix dancehall and dub into hip-hop, drum'n'bass, and bhangra for their "Beat Research." Meanwhile, Dublin House in Dorchester offers "Sexy Tuesdays" with Cannon Movements, "Weddi Weddi Wednesdays" with Riddim Rider, and "BoomBlast Thursdays" with Junior Rodigan. Live acts, from Mang Dub to Toussaint to III Kings to Dub Station to Vibewise, fill clubs and pubs around town, and local selectors such as Jah Rich, DJ Advance, and Mad Skim throw occasional sessions and host semi-annual soundclashes at spots from the Western Front to Kay's Oasis in Dorchester. Every weekend there are special events of all kinds and all sizes, from dances to concerts, often drawing performers and soundsystems from New York to Jamaica and usually involving a fun dress code of sorts. Although many record collectors bemoan the physical closing of Beehive Culture, there's still Taurus Records and Junior Rodigan's Vibes Records for those seeking the latest and greatest tunes.

Being both far from "home" and yet among neighbors, Boston's Caribbean community has cultivated and celebrated a pan-Caribbean identity. Given shape in music, dance, and other cultural forms, Boston's "island heritage" resonates across the city's soundscape. That we can all partake in such a rich diaspora of sounds is a privilege no Bostonian should forsake.

Wayne Marshall is a writer, teacher, and performer living in Cambridge. He would like to big up “dancehall lover” and “sexcd” @ bostonreggae.com, and give special thanks to Junior Rodigan, for supplementing his hazy recollections with those of some local veterans.